Selected Writings 2008-2024

Haidar al-Ghazali

I don’t want to upset you with this note, but I’ve learned that writing can explode this weight off my chest, and that whoever reads my pain carries away a small part of it. I’m sorry the choice fell on you, but something tells me that you can act upon this world. >>>>

Haidar al-Ghazali

Elegy for Fatima Hassouna, April 17 2025

Fatima asked me to write her epitaph. A heavy task no text can fulfil.

I don’t believe that Fatima has gone or that this city will lose one of its clearest voices.

I don’t believe it because Fatima suits life: the dreams she drew, step by step, image by image, poem by poem, song by song.

I don’t believe it. >>>>

Robyn Maynard & Leanne Betasamosake Simpson

Why we boycott Israel: ‘One day everyone will have always been against this’

As Black and Indigenous women, respectively, we hail from transnational political traditions that have supported people trying to survive under regimes of racial hierarchy, apartheid, and militarized violence from Canada to Haiti to South Africa. Signing this letter continues in the spirit of these traditions.

Emerging from human rights struggles in the late 1960s, cultural boycotts were part of a larger popular anti-apartheid boycotts movement which, over the course of 30 years, helped bring about the end of apartheid in South Africa. >>>>>>>>

Mirza Waheed

They’re Screening an Adaptation of My Novel in an Israeli Settlement, So I’m Boycotting It

Last week, more than 5,000 writers and publishers from across the world pledged not to work with “Israeli cultural institutions that are complicit or have remained silent observers of the overwhelming oppression of Palestinians.” The pledge may be the biggest single act of cultural boycott since the mobilization against apartheid South Africa. The list of signatories includes some of the world’s most well-known and loved writers. I was also one of the signatories. >>>>

Ta-Nehisi Coates

The Message is a book for young writers, and as such, I have a matchmaker’s interest. And so in that interest—and well aware that my critique of Zionism and its effects will invite some scrutiny—I have compiled a rough account of my sources and references for the book’s final essay, “The Gigantic Dream.” >>>>

Nesrine Malik

I Wish you could see the Living Nightmare in Palestine.

I began to write this column last week in Ramallah in the occupied West Bank. I started it several times, both on the page and in my head, as I travelled between occupied territories. In every location I started the column again, then failed to capture what is unfolding and has been for years. >>>

Ta-Nehisi Coates

Last summer I spent ten days traveling the lands under Israeli rule. What I saw was hauntingly familiar. For as sure as my ancestors were born into a country where none of them was the equal of any white man, Israel is a state where no Palestinian is ever the equal of any Jewish person. In Israel itself, I met with Palestinians who were nominally empowered, with the right to vote. But unlike their Jewish countrymen, these Palestinians could not pass on their citizenship to spouses and children. Moreover, discrimination against them was perfectly legal. Frequently they were the subject of outright racism, as when Netanyahu warned his country during the 2016 election that “the right-wing government is in danger. Arab voters are heading to the polling stations in droves.” >>>>

Tareq Baconi

Confronting the Abject: What Gaza Can Teach Us About the Struggles That Shape Our World

We each carry within us a degree of self-loathing. A true self that is, knowingly or otherwise, hidden from the world in shame. In fear, also, that it might elicit judgement, or disrupt the norms around us that we are socialized into and come to abide by. Within every Self, there is an Other that is trampled on, marginalized, and suppressed in the anxious belief that its acknowledgement might destabilize the Self and bring it to ruin. That is to say, we are all, on some intimate level, familiar with abjection, with the wretchedness we feel at confronting the Other within or around us. The abject being, of course, all that is disgusting, repulsive, ugly, unfit to be in proper society, exceptional, subhuman. >>>>

Their Borders, Our World

Their Borders, Our World is an anthology thoughtfully arranged and introduced by PalFest co-curator Mahdi Sabbagh.

Contributors include: Yasmin El-Rifae, Jehan Bseiso, Keller Easterling, Dina Omar, Tareq Baconi, Samia Henni, Omer Shah, Kareem Rabie, Ellen Van Neerven, Omar Robert Hamilton and Mabel O. Wilson.

Each piece grapples with the questions: How do we confront the need to take inevitable and often difficult political stances? How do we make sense of the destruction, uprooting, and pain that we witness? And given our seemingly impossible reality, how is mutuality constructed? >>>>

Pankaj Mishra

In 1977, a year before he killed himself, the Austrian writer Jean Améry came across press reports of the systematic torture of Arab prisoners in Israeli prisons. Arrested in Belgium in 1943 while distributing anti-Nazi pamphlets, Améry himself had been brutally tortured by the Gestapo, and then deported to Auschwitz. He managed to survive, but could never look at his torments as things of the past. He insisted that those who are tortured remain tortured, and that their trauma is irrevocable. Like many survivors of Nazi death camps, Améry came to feel an ‘existential connection’ to Israel in the 1960s. >>>>

Benjamin Moser

The Washington Post, January 2 2024

Before World War II, Zionism was the most divisive and heatedly debated issue in the Jewish world. Anti-Zionism had left-wing variants and right-wing variants — religious variants and secular variants — as well as variants in every country where Jews resided. For anyone who knows this history, it is astonishing that, as the resolution would have it, opposition to Zionism has been equated with opposition to Judaism — and not only to Judaism, but to hatred of Jews themselves. But this conflation has nothing to do with history. Instead, it is political, and its purpose has been to discredit Israel’s opponents as racists. >>>>

Michelle Alexander

This essay is adapted from a speech given at the Palestine Festival of Literature on Nov. 1, 2023.

Good evening. My name is Michelle Alexander. I am a former visiting professor and current student at Union Theological Seminary. I am so glad to be with all of you tonight. There is nowhere on earth that I would rather be at this moment in time. Thank you all for showing up. The fact that so many people are here tonight from all different religions, races, ethnicities, and genders is itself a testament of hope. I know that so many of us are carrying a great deal of grief, fear, anger, internal conflict, and despair into this room. I hope that we can breathe together now that we have arrived, exhale, open our hearts to one another, and listen deeply to each other. We are here. We are many. And we are not alone. >>>>

Rickey Laurentiis

TALL LYRIC FOR PALESTINE (OR, THE HARDER THINKING)

Because I should’ve wrote this years

ago, I’m crying. So what my slow

failure pass the years

Make me be crying. So what in

Bethlehem I tried to push so much

against it, where the Wall is

checkpoint and weird. So what

An Open Letter from Participants in the Palestine Festival of Literature

NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS | 14 October 2023

“We are writers and artists who have been to Palestine to participate in the Palestine Festival of Literature. We now call for the international community to commit to ending the catastrophe unfolding in Gaza and to finally pursuing a comprehensive and just political solution in Palestine. We have exercised our privilege as international visitors to move around historic Palestine in ways that most Palestinians are unable to. We have met and been hosted by Palestinian artists, human rights workers, writers, historians, and activists. We have stood on stage with them. Many of these people, including the festival organizers based in Palestine, are in fear for their lives right now. One festival organizer is locked down with their child in Ramallah, sharing updates about the people killed by armed settlers last night. One partner in Gaza, a magazine editor, is no longer answering messages.” >>>>

Molly Crabapple

I spent the end of May and the beginning of June in the West Bank and occupied East Jerusalem, first as a guest of the Palestine Festival of Literature, and then documenting daily life in my sketchbook. It had been eight years since my last trip to Palestine, and on the face of it, everything had gotten worse. The contradictions that plague any ethnonationalist project had all come to a bloody head with the reelection of Netanyahu last fall and his appointment of openly fascist ministers Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich, who have been encouraging settler rampages across the West Bank. Yet in some ways the oppression is just more obvious now. The checkpoints still resemble cages. The bombs still fall on Gaza. The West Bank Wall, that monument to cowardice erected after the second intifada, still defaces the land. The grind of petty state aggression—of permit denials, intrusive searches, and arbitrary rules—still provides the backdrop for outbreaks of spectacular violence by Jewish settler organizations and the military, which often work in concert. On Monday, the Israeli Defense Forces launched a full scale invasion of the Jenin refugee camp in the West Bank with airstrikes, drones, and armored bulldozers, killing at least twelve Palestinians, injuring a hundreds, and forcing three thousand people from their homes.

“We have on this land all of that which makes life worth living,” wrote Mahmoud Darwish, Palestine’s national poet. The land remains, its terraced hills trashed with plastic bottles and softened with wild za’atar, its stone walls, its swaggering hustlers, its wry old ladies exhausted and indomitable, their glittering laughter, their generosity and contempt. What else makes life worth living, according to Darwish? The conqueror’s fear of memory. The tyrant’s fear of song. >>>>

A Party for Thaera

Various Authors, Edited by Haifa Zangana; 2021

"In a first, nine politically-diverse women, former Palestinian political prisoners, sat around a table in a small room in Ramallah, in the occupied West Bank, to share their stories of incarceration. These non-writers learnt to express the reality of their time in prison, of the separation from their children, of the endless struggles against Israeli occupation, to produce heartfelt narratives that go beyond simply recalling the details of their sentence or revisiting their trauma. Instead, this unique volume transforms their experiences into an expression of the self, giving readers an “exceptional” insight into an almost unknown women’s world, of life and love behind bars and beyond.”

Edited by Haifa Zangana and published by Ritu Menon of Women Unlimited after attending PalFest.

Ashish George

On my way to the 2019 Palestine Festival of Literature, the flight presents me with a unique opportunity. In a precious interlude between hassles, I get to exist in close proximity to people without them knowing about my disability. Most passengers are too distracted or too bleary-eyed to notice a wheelchair user’s early boarding, so when they take their seats they see the person next to them as a frustrated equal, nothing less and nothing more than a fellow repository of bones and flesh who would rather still be in bed. But to a lifelong paraplegic, the cabin of an airplane is the stage of a poignant, if somewhat cramped, ballet. >>

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Palestine. How I wish I could be there with the Palfest 2020 writers’ delegation. It has been a life-long dream for me to visit Palestine since I was eighteen.

Let me tell you a story about how a tenant farmer’s daughter—I—from rural Oklahoma came to know about Palestine and the 1948 Nakba as a teenager in the mid-1950s... »

Mahdi Sabbagh

THE FUNAMBULIST, DECEMBER 2019

The cultural siege is bi-directional: it isolates Palestinians from the rest of the world while muddying outsiders’ understanding. The idea of solidarity is often demoted to secondary importance behind urgent questions of humanitarianism. We reject this elision and work to create connections of mutual solidarity, of intellectual exchange, of committed artistic production. We work to highlight not only what is happening in Palestine, but how it intersects with anti-colonial and anti-capitalist struggles around the world.

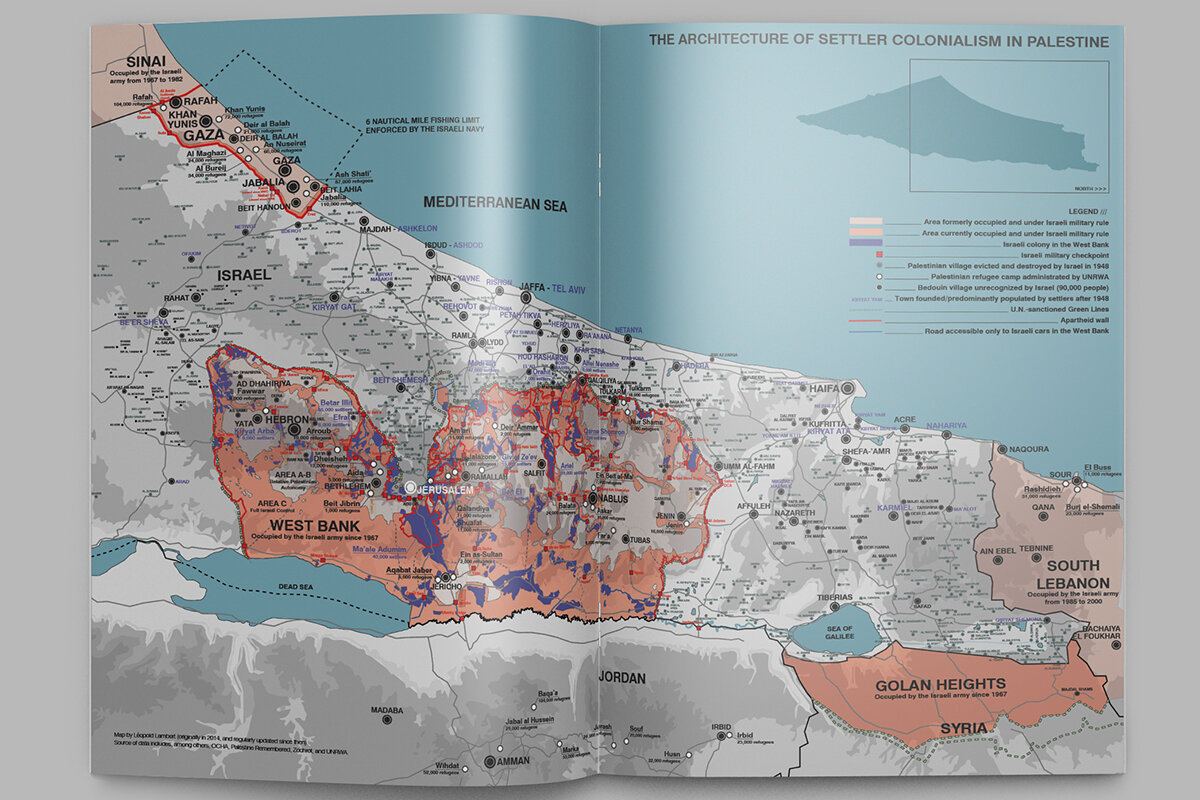

What does colonial rule look like? What is its architecture? »

The Funambulist

ISSUE 27: Learning with Palestine

Issue-length collaboration with the Funambulist Magazine with “contributions by five PalFest 2019 guests, three PalFest organizers, and four guest Palestinian authors around one question: how to reclaim what colonialism stole? Cities (Mahdi Sabbagh), land (Nick Estes & Maath Musleh), language (Jehan Bseiso & Karim Kattan), interiors (Victoria Adukwei Bulley & Sabrien Amrov), narratives (Samia Henni & Mostafa Minawi), and digital instruments (Madiha Tahir & Majd Al-Shihabi) constitute the core components of the various answers formulated around this question.”

300 Authors

LONDON REVIEW OF BOOKS, SEPTEMBER 2019

It is with dismay that we learned of the decision of the City of Dortmund to rescind the Nelly Sachs Award for Literature from Kamila Shamsie because of her stated commitment to the non-violent Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement for Palestinian rights. »

بالفست

ولذلك، نعود اليوم بنسخة الاحتفالية لعام ٢٠١٩ بعد استراحة عامٍ كامل لنركز جهودنا على رعاية كتابات جديدة توضح وتؤطّر للروابط بين استعمار فلسطين وأنظمة السيطرة والسلب المتسارعة حول العالم.

PalFest

We return now, after a one-year break, with PalFest 2019 and a sharpened focus on how to foster new writing that clarifies and frames the connections between the colonization of Palestine and the accelerating systems of control and dispossession around the world. »

Ahdaf Soueif: Jerusalem

THIS IS NOT A BORDER, (Bloomsbury, 2017)

I was not prepared. Who could have been?

Remission Gate. There were two Israeli soldiers in the gateway.

It was December 2000 and the second Intifada was in full swing and there were soldiers everywhere. At least here they were on foot; at Damascus Gate they’d been mounted. I walked through the gateway into the Sacred Sanctuary of al-Aqsa – and a few enclosed acres became a world. At my back the city behind the walls, but in the great sweep ahead there were tall, dark pines, broad steps rising to slender white columns and, beyond them, a golden dome and the biggest sky I had ever been under. »

February 24, 2020. REUTERS/Danish Siddiqui

Pankaj Mishra: India and Israel

THIS IS NOT A BORDER, (Bloomsbury, 2017)

India did not have diplomatic relations with Israel until the 1990s. My grandfather was among many high-caste Hindus who idolised Israel because it possessed, like European nations, a proud and clear self-image; it had an ideology, Zionism, that inculcated love of the nation in each of its citizens. Most impor- tantly, Israel was a superb example of how to deal with Muslims in the only language they understood: that of force and more force. India, in comparison, was a pitiably incoherent and timid nation-state; its leaders, such as Gandhi, had chosen to appease a traitorous Muslim population. »

This Is Not A Border

REPORTAGE & REFLECTION FROM THE PALESTINE FESTIVAL OF LITERATURE (BLOOMSBURY, 2017)

This Is Not a Border: Reportage & Reflection from the Palestine Festival of Literature is a collection of essays, diaries and poems collected over the festival’s first decade.

47 authors, 44 essays, 17 poems…

Natalie Diaz

I read “Whereas” alongside a book called “Architecture After Revolution” (2013) while in Palestine with a group of international writers traveling daily across the borders between Israel and the West Bank. “Whereas” was in my bag and on my mind while navigating the psychological and physical experiences of Israeli occupation of Palestine, which were recognizable to me, having grown up at Fort Mojave, a military fort turned reservation. It is easy to forget that America is an occupied land unless you are familiar with the hundreds of treaties made between the United States government and over 560 federally recognized indigenous tribes across our nation.

بالفست

في هذه السنة تدخل احتفالية فلسطين للأدب، بالفِست، سنتها العاشرة.

نحن في عام ٢٠١٧، لكننا لا نزال نعيش في القرن العشرين.

لن يتقدم التّاريخ، ولن تتفكك الامبراطوريّات، حتى تنال فلسطين حريّتها.

لا يمكن لأحدٍ منّا أن يكون حرًا حتى تكون فلسطين حرة. هذا إيماننا منذ البداية.

عشر سنواتٍ مرّت منذ أن أقامت الاحتفاليّة أولّ فعاليّةٍ لها في “المسرح الوطني الفلسطيني” في القدس المحتلة. عشرة مهرجاناتٍ، عشرة تدخلاتٍ صغيرةٍ في عقدٍ مكثف الألم؛ عقد شَهِد الاعتداءات المتكررة على غزة، وحصارٍ عليها كحصارات القرون الوسطى، عقدٍ شهد الانتفاضات والثورات العربية – وثوراتها المضادّة، شهد ترسيخ الحرب الأبدية وتمزيق أحشاء سورية، عقد صعد فيه نجم داعش وبوتين وترمب ومن يتبعهم.

PalFest

The year is 2017 and this is now the tenth annual Palestine Festival of Literature. The year is 2017 and yet we are still living in the 20th century. History cannot move forward, empires cannot be dismantled, until Palestine is free.

None of us can be liberated until Palestine is free.

This we have long believed.

Ten years have passed since PalFest staged its first event at the National Theatre in Jerusalem. Ten festivals, ten tiny interventions in a terrible decade that has witnessed three assaults and a medieval siege on Gaza, the rise of the Arab revolutions and their counter-revolutions, the entrenchment of the Forever War, the evisceration of Syria, the rise of ISIS, Putin, Trump and their vassals.

Nancy Kricorian

THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY, JUNE 2017

B, a priest I meet at a church supper in Virginia during my book tour, tells me that when he was a seminarian in Jerusalem in the early 70’s, the Haredi Jews spat on the Armenian priests on a daily basis – and on the seminary students. He says: “One day I just got fed up with it. I called the other seminarians together—there were five of us—and we agreed that we’d undo our belts and keep the belts and our hands inside our cassocks. We walked out of the church and a man spat on us, and we pulled out our belts and gave him a thrashing. It might not have been the Christian thing to do, but I was young then and it was satisfying.

Yasmin El-Rifae

Houses in Jerusalem’s old city are small and built on top of one another, sharing courtyards and terraces. What begins as a simple entryway on the street opens upwards and outwards. Stairs take you around one home, and to the door of another. A tunnel-like passageway leads to a circular landing that offers doors to four different homes.

Laila Lalami

I had gone to Palestine fully expecting to see occupation and degradation, but I had not expected to witness my own privilege so swiftly or so starkly. My birth in Morocco had made the Moroccan-Israeli immigration official see me for who I was, while Ahmed Masoud’s birth in Palestine had been enough to strip him of his individuality, enough to make the immigration official label him a threat.

Ahdaf Soueif

THE TIMES LITERARY SUPPLEMENT, JANUARY 2016

The thin, spiky line that looks like barbed wire runs westward across the lower half of the page. It cuts between Deacon’s Hill and the East Lake, then between The Gardens and Um Hamdan. It pauses at Shatta railway station then runs on past the Police Post and off the page. This is p273 of Salman Abu Sitta’s massive Atlas of Palestine (2010) which, together with Walid Khalidi’s All That Remains (1992), provides a comprehensive map of a world about to be overlaid and concealed by the application of Zionism. »

Molly Crabapple

The army does not permit the 25-year-old to lock his doors, and when soldiers use the watchtower during the day, they lock Sayeed's family in their rooms. His home, like many others in the area, is subject to frequent night raids in the name of security—in other words, investigation accusations of rock-throwing or other terroristic actions. (Throwing a stone at a moving vehicle is now punishable by up to 20 years in prison thanks to a new law that has been derided by its critics as racist against Palestinians.) Sayeed told me he'd been arrested many times; he lifted up his pant leg to show me scars he said came form beatings at the hands of the authorities.

Omar Robert Hamilton

At the border it is always the same questions. Do you have another name? Do you have another passport? What is your father’s name? What is his father’s name? Have you ever been to Syria? Lebanon? Morocco? What are you doing here?

I used to feel sick for days before coming to Palestine. Would rehearse my answers, shut down my Twitter page, print off hotel reservations, eject SIM cards. I spent four years’ worth of interrogations claiming to be making a film about the restoration of a church in Nazareth. This time, I would think each time, they will Google me. This time, the Israelis will turn me away.

Molly Crabapple

Nearly a year after the end of Protective Edge, little has changed in Shujaiya. A few houses have been patched up, but many more are nothing but rubble. Piles of prescriptions fluttered in front of the destroyed Ministry of Health. Everywhere homes lay collapsed like ruined layer cakes, the fillings composed of the flotsam of daily life: blankets, cooking pots, Qu'rans, cars. In one pile of dust I saw a child's notebook, abandoned. "My uncle collects honey," the nameless child had written on the first page.

Teju Cole

Not all violence is hot. There’s cold violence too, which takes its time and finally gets its way. Children going to school and coming home are exposed to it. Fathers and mothers listen to politicians on television calling for their extermination. Grandmothers have no expectation that even their aged bodies are safe: any young man may lay a hand on them with no consequence. The police could arrive at night and drag a family out into the street. Putting a people into deep uncertainty about the fundamentals of life, over years and decades, is a form of cold violence. Through an accumulation of laws rather than by military means, a particular misery is intensified and entrenched. This slow violence, this cold violence, no less than the other kind, ought to be looked at and understood.

Ed Pavlic

AFRICA IS A COUNTRY, JULY 2014

In the weeks since returning from the West Bank I’ve been tuned into the news, the news that stays news, and the news that isn’t news at all. The top story in the The New York Times on Wednesday, July 9th begins “Israel and Hamas escalated their military confrontation on Tuesday. . .” Inches away, the World Cup story allows, “The final score was Germany 7, Brazil 1. It felt like Germany 70, Brazil 1.” The juxtaposition of balance on one hand and the exaggeration of how unbalanced the World Cup rout felt on the other is too close to ignore. I dare say, with warfare again in the open in the region, it’s worth tracing its contours in our media, in our minds, and in our lives.

China Miéville

“So we should ask Mohammed Al-Durra. He isn’t dead again.

Recall his face. Even from a government one of the chief exports of which is images of screaming children, his was particularly choice, tucked behind his desperate father, pinned by fire. Until Israeli bullets visit them and they both go limp. He for good. Pour encourager les autres.

Now, though, thirteen years after he was shot on camera—one year more than he lived—he has been brought back to life. But wait before you celebrate: there are no very clear protocols for this strange paper resurrection. Mohammed Al-Durra is a bureaucratic Lazarus. After a long official investigation, by the power vested in it, the Israeli government has declared him not dead. He did not die.”

William Sutcliffe

I returned from Palestine psychologically and emotionally devastated by what I had seen. Every aspect of the occupation was harsher, more brutal than I had expected. For months, I couldn't even look at the draft of my novel. The idea of treating this topic too lightly, of not doing justice to the suffering I had witnessed, filled me with shame. I knew I had to make the next draft of the book resemble the West Bank more closely, but I also knew it had to retain some distance from reality for the novel to function as fiction.

Gary Younge

Since 2005, a massive rebranding campaign has taken place to dispel Israel's reputation for religiosity and war and portray it instead as the home of "creative energy". The trouble is, since then there has been the bombing of Lebanon, the Gaza blockade, the attack on a Gaza aid flotilla, and the escalation of illegal settlements.

To suggest that Palestinians are equally responsible for this state of affairs would suggest the two sides hold equal power to shape events. They don't. No matter how many rhetorical checkpoints get thrown up, there are some basic facts you just cannot get around. Israel is the occupier; Palestinians are the occupied.

Jeremy Harding

LONDON REVIEW OF BOOKS, JUNE 2009

These raw presentations were worked up in roughly fifteen minutes; some contained the kind of detail you’d only expect to come with the finishing touches. What if we’d had more time? But time in the West Bank is eaten up by the byzantine demands of the occupation, which interfere with everything, including sitting finals - any moment now. The rucksack, I notice, as the owner shrugs it onto her back, is full to capacity.

Henning Mankell

STOPPED BY APARTHEID

“För en dryg vecka sedan besökte jag Israel och Palestina. Jag ingick i en författardelegation med representanter från olika kontinenter. Vi skulle medverka i en palestinsk litterär konferens. Invigningen skulle ske på den Palestinska Nationalteatern i Jerusalem. Just när vi hade samlats kom tungt beväpnad israelisk militär och polis och meddelade att dom tänkte stoppa oss. På frågan varför, var svaret:

– Ni utgör en säkerhetsrisk.

Det är naturligtvis nonsens att påstå att vi i det ögonblicket utgjorde ett terroristiskt hot mot Israel. Men samtidigt hade dom ju också rätt. Visst utgör vi ett hot när vi kommer till Israel och säger vad vi tycker om israelernas förtryck av den palestinska befolkningen. Det är inte konstigare än att jag och tusentals andra en gång utgjorde ett hot mot apartheidsystemet i Sydafrika. Ord är farliga.'“

Claire Messud

It has been a week of unimaginable experiences: from the hours waiting at the crossing at Allenby Bridge, to the agonizing descent into darkness that was our visit to the old city of Hebron – a place of architectural and historical magnificence now blighted by sectarian violence and by a quotidian oppression that must be experienced, even for a few hours, to be believed. But I, at least, had naively imagined that our return to Jerusalem would entail some return to the world as I thought I knew it, to some relief from the Kafkaesque madness that is life under occupation. »

Suheir Hammad

….h, i, j, k, l.

between “k” and “l” no thing. air. space.

a walk. a wall. a walk.

raja shehadeh is a walker and a trail blazer, but not a tour leader. we walked and climbed and slid and sometimes crawled through the hills in our city slicker clothes. we held each other’s hands as we made ways up and then down. thorns everywhere. settlements on highest ground, and the sun behind clouds. sumac and zaatar and maramiya growing. terraced hills.

the israeli settlers from nearby colonies get to walk in these hills unmolested. the palestinians do not. the beauty and energy of the land, i imagine, has no political motivation, unless the desire to be loved and appreciated is political. it is here.

i wonder if soil has heart. i wonder if blood, sweat, and tears do feed roots and flower fruit. if the earth itself has memory, and can she remember, somehow, all those who came and planted and ate here. especially, as i struggle through the climb, i think of the women in traditional gear, expected roles, clmbing with broad steady feet these steps in the hills. i wonder if some people are walking phantom limbs looking for home.

*suad amiry this evening talks about how she gets lost in the west bank, when once she knew it like her hand. so many checkpoints and detours where once there were open roads. “space and time here is not what you think,” she says and i understand. what once took 20 minues now takes ten times the time. where there was space to plant and even bbq and picnic, there is now…the space is still there but it’s no longer accesible. so “here” and “now” mean different things in this place.

*in ramallah i get to see many friends who come out for the festival’s evening event. i ask them each, how has the year been, and the answers are the same, and in an order. first they respond, “alhumdilallah” or something like it, meaning “thank god/all good”. then they ask how i am. then i ask again and the answer is something along the lines of “not bad”. ask again, and the truth comes, and the truth here, now, is beautiful and hard, like the land we walked.

*there is a wall.

here is a land.

now is the time.

the people are here.

still.

Andrew O’Hagan

LONDON REVIEW OF BOOKS, JUNE 2008

Last week, from my window at the Pilgrim Deluxe, Bethlehem initially looked just as it should. The hills in the distance were grey and blue and unmarked by passing arguments. ‘This was once the more prosperous end of town,’ our guide said. ‘But the wall has ended all that. The town cannot grow and the Palestinians are not allowed to look at their own horizon. We are caged here, that is the story.’

Ian Jack

How could the "peace process" begin to dismantle what Ariel Sharon called these "facts on the ground"? Nobody knows. Sharon himself is being kept alive at vast expense in an Israeli hospital (Palestinian joke: "Is Sharon alive or is he dead?" "Neither, he is still going through the checkpoints.") In fact, no Palestinian I met believed in the peace process, "a process gyrating in an empty circle" in the words of the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish.

Mahmoud Darwish

WELCOME LETTER TO THE INAUGURAL PALESTINE FESTIVAL OF LITERATURE

Dear Friends,

I regret that I cannot be here today, to receive you personally.

Welcome to this sorrowing land, whose literary image is so much more beautiful than its present reality. Your courageous visit of solidarity is more than just a passing greeting to a people deprived of freedom and of a normal life; it is an expression of what Palestine has come to mean to the living human conscience that you represent. It is an expression of the writer’s awareness of his role: a role directly engaged with issues of justice and freedom. The search for truth, which is one of a writer’s duties, takes on – in this land – the form of a confrontation with the lies and the usurpation that besiege Palestine’s contemporary history; with the attempts to erase our people from the memory of history and from the map of this place.